Dr. Parveen Azam: Battling Pakistan’s Drug Epidemic

Written by: Aiza Azam

Dr. Parveen Azam is a pleasure to meet. Soft-spoken, graceful, and elegantly attired, she has the compassion of a Mother Teresa and the courage of a lioness. Working tirelessly to effect change from a multidimensional approach, she is on the board of the Pakistan Primary Healthcare Initiative, on the Child Protection Welfare Commission created by the Parliament, and is also involved with prison reforms. For the past 23 years, she has devoted herself to working on an issue that no one else is willing to address: rehabilitation of the country’s teeming masses of drug addicts. The head of a Peshawar-based not-for-profit institution called the Dost Foundation, Dr. Azam and her team undertake a task that involves heartbreak and victory in equal measure.

She identifies herself as a missionary doctor, and the seed for her life’s work was planted when she was a young boarder at the Convent of Jesus and Mary in Murree. “It was a different time; we lived in a dream world, our own bit of heaven. The way we were taught is very different from what teaching has become today.” Her teachers, whom she refers to as the students’ “psycho-social parents”, lavished attention on their charges and imbued them with high ideals. In an environment of missionaries working to uplift marginalized communities, she decided to work with lepers, whom she considered the most ostracized section of society.

Dr. Azam’s father, Dost Mohammad Khanzada, held emancipated views and wanted all his daughters to have a good education. She had wanted to pursue a career in law, but he insisted she become a missionary doctor. “My father told me, ‘I’ll build you a hospital, provide you a salary and buy you a car so you can travel to different communities and work with the poorest of the poor.’” Her maternal grandfather was also a medical doctor, with an MBBS from King Edward Medical College in Bombay, and was an important role model for the family’s children. Dr. Azam’s father passed away at the young age of 45. In December 1954, she graduated from the Convent, carrying her father’s dream with her.

After graduating from Fatimah Jinnah Medical College in 1961, she joined the civil service the following year and went to work for the NWFP government. Her work in primary healthcare necessitated traveling to far-flung and neglected areas, working with communities at the grassroots level in villages, valleys, and on mountaintops. In 1988, she retired from civil service but continued to practice. Around this time, she increasingly felt that she hadn’t gotten a chance to serve the marginalized communities, which was actually the reason why she had initially become a doctor.

By 1992, drug addicts had become a common sight on the streets of Peshawar, but suddenly, one day, they all seemed to have disappeared. She found that the police had begun rounding them and throwing them in prison or dumping them outside the city. Eventually, they began congregating at Karkhaana Market (the smugglers’ market), which did not fall under police jurisdiction. There, she discovered a big compound with some 300 addicts, including women and children; a number of dead bodies were also lying around, some half-eaten by jackals. “They were totally dehumanized. I felt very strongly that I needed to help them, to try and give them some dignity.” Along with a small team, she began digging shallow trenches in the area to try and give the dead a decent burial; she would also conduct on-site counseling sessions. Initially, the addicts found it hard to believe that the people helping them had no expectation of a return; they were used to being ostracized, and facing abuse and mistreatment at the hands of agents of the system.

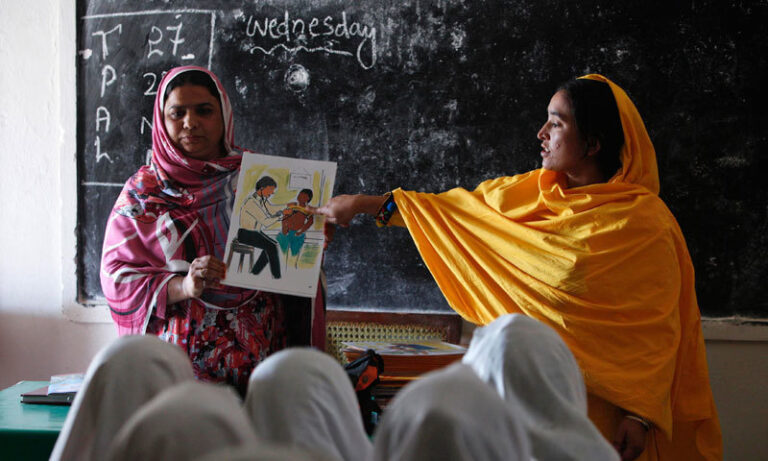

Dr. Parveen Azam at one of Dost’s health clinics

Gradually, Dr. Azam and her team built up a foundation of trust, but not without its share of challenges. Early on, they were threatened by the drug mafia. “The compound was surrounded by shops selling ammunition and drugs; the owners began aerial firing when we arrived one day because we were taking their clients away. We continued undeterred.” Another time, the team arrived to discover that all the addicts had disappeared. Someone had spread rumors that Dr. Azam and her team would take them all away and sell their organs. It took some convincing to quash this lie and re-engage. Within a short time, however, the addicts were voluntarily seeking Dr. Azam’s team for help. As numbers continued to grow with time, they took a bungalow in the Hyatabad area and began their first in-patient, outpatient program.

Dr. Azam explains that the institution was named after her father. “He gave me his legacy of being a friend to the friendless,” she says.

Since its humble beginning in 1992, Dost Foundation has certainly come a long way. Its campaign for a drug-free Pakistan has continued to prosper over the last 23 years and shows no signs of slowing down any time soon.